Why many tax-exempt organizations are shifting from 457(f) plans to split dollar SERPs to manage tax exposure, compliance risk, and retention.

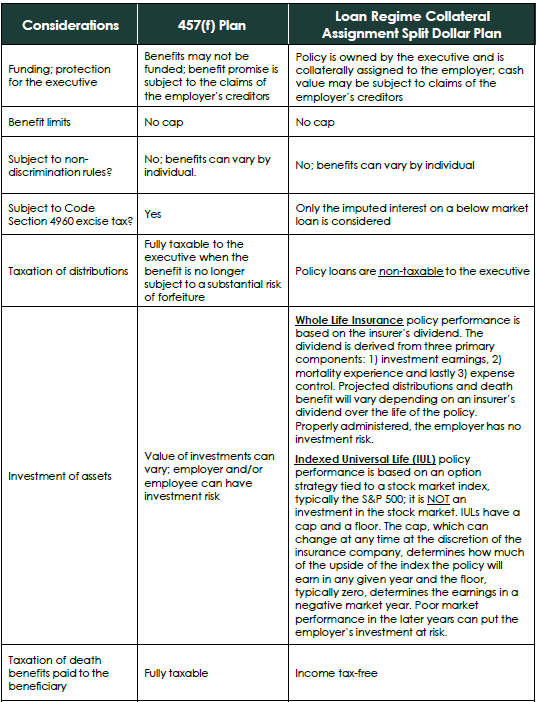

For many years, the go-to form of supplemental retirement benefits for an executive of a non-profit organization1 has been a 457(f) plan. The benefits under a 457(f) plan are taxable to the executive in the first year in which they become “vested,” even if the benefits are not payable to the executive until a later date.

Perhaps even more problematic is the excise tax of 21%, paid by the employer, on excess compensation that was added as part of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. The excise tax materially increases the cost to any tax-exempt organization with a 457(f) plan that is expected to provide a benefit to a covered employee over $1 million or that could result in an excess parachute payment.

Due to the limitations of a 457(f) plan, coupled with the extra cost potentially imposed by the excise tax, many non-profit organizations are considering split dollar life insurance arrangements as a vehicle to provide supplemental retirement benefits to executives.

Split Dollar Life Insurance

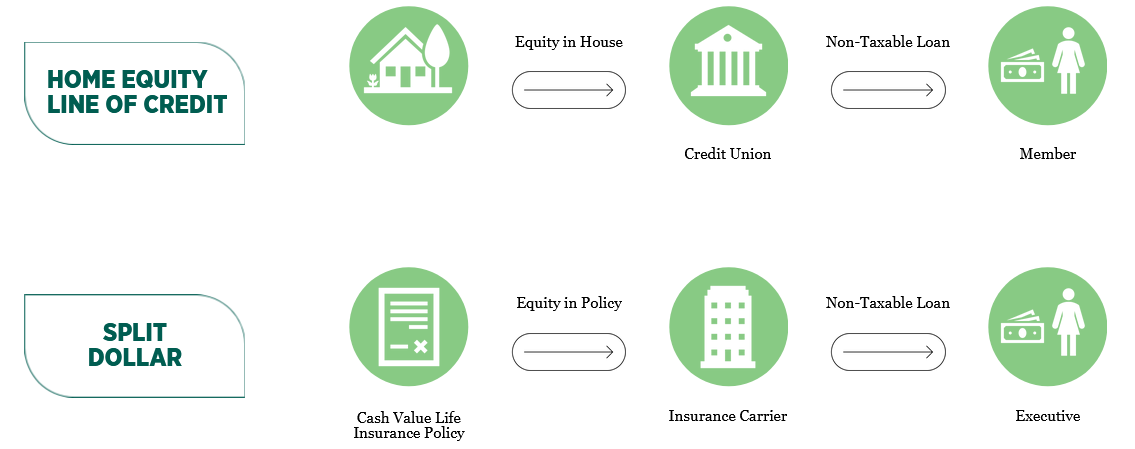

A split dollar life insurance arrangement is an arrangement where the benefits and obligations with respect to a life insurance policy are split between the employer and the employee. Split dollar life insurance arrangements may be taxed under the “loan regime” rules (where the executive owns the policy) or the “economic benefit” rules (where the organization owns the policy.) Under a special rule, if the executive owns the policy but only has the right to a portion of the death benefit (in other words, it is a “non-equity” arrangement), the executive is taxed under the “economic benefit” rules on the value of the death benefit each year. The agreement can also be structured as a “switch dollar” arrangement, which begins as a “non-equity” arrangement and at some point in the future, converts or switches to a collateral assignment loan regime split dollar agreement.

Loam Regime Split Dollar Arrangements

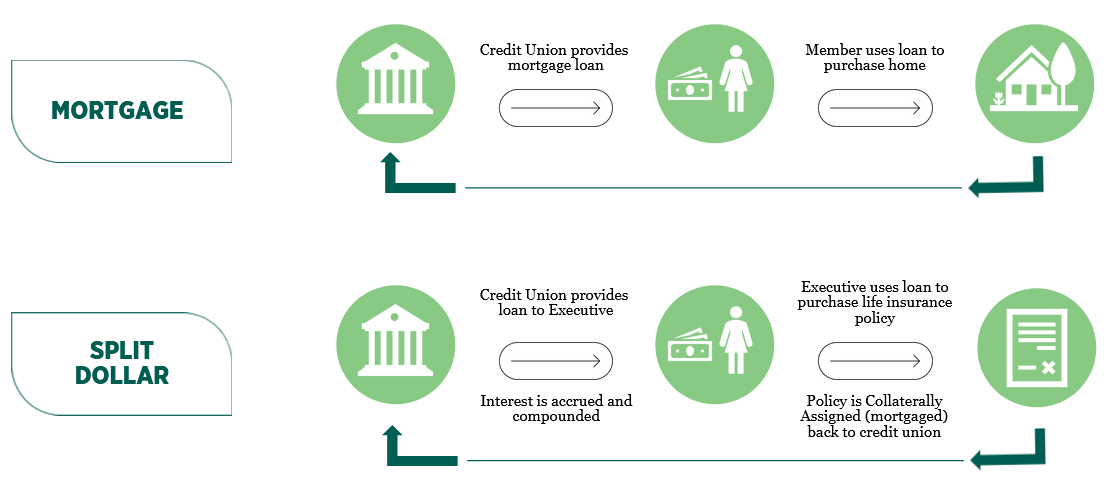

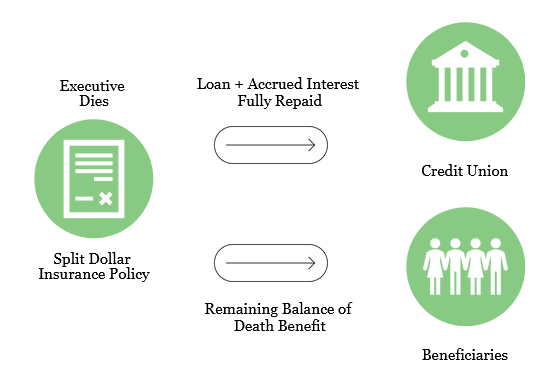

In a loan type split dollar arrangement, sometimes called a “collateral assignment split dollar,” the executive owns the policy and the employer pays the premiums for the executive’s benefit in the form of a loan to the executive. The death benefit is split between the employer and the executive’s beneficiaries. The employer typically recovers the premium payments (and generally interest that has accrued on the loan) from the death benefit. A loan to an executive under a collateral assignment split dollar agreement is similar to a mortgage loan, where the employer is the lender and the executive is the borrower.

The executive may be allowed to take loans from the policy, typically at retirement age, in amounts that do not impair the employer’s right to be repaid. Loans from the policy are non-taxable to the executive.

The loan from the employer may be structured as a demand loan (payable on demand) or a term loan (typically payable at the executive’s death). If the loan bears interest below the applicable federal rate (“AFR”), it will be considered a “below market” loan and the executive will need to recognize imputed income over the life of the loan. An advisor can assist the employer in evaluating the impact of the different types of loans and whether to charge interest on the loan at or below the AFR.

Economic Benefit Regime Split Dollar Arrangements

In a split dollar arrangement taxed under the “economic benefit” rules, the employer owns the policy. The executive has the right to a portion of the death benefit (typically the amount in excess of the premiums paid by the employer) and may also have the right to some or all of the cash value of the policy. The executive is taxed each year on the value of the economic benefits provided to the executive under the policy, which may include the value of the death benefit and the annual increase in the cash value of the policy.

“Switch Dollar” Split Dollar Arrangements

In a “switch dollar” split dollar arrangement, the executive owns the policy, but only has the right to a specified amount of the death benefit. The employer has the right to the remainder of the death benefit and all of the cash value. Because the executive has no rights in the equity (cash value) of the policy, it is initially taxed to the executive under the “economic benefit” rules. Under those rules, the executive is taxed on the value of the death benefit each year. At some time in the future specified in the agreement (which may be a designated year or upon termination of employment or retirement), the executive is given the right to convert the arrangement to a loan regime split dollar agreement. Upon conversion, the executive signs a promissory note agreeing to repay the employer for the greater of the premiums paid (including any premiums that are pre-funded) or the then cash value of the policy, which amount bears interest from that point; the parties enter into an amended split dollar agreement; and the loan regime rules take effect.

A switch dollar agreement may be an attractive option when interest rates are high. The arrangement is initially taxable to the executive under the economic benefit rules and can be converted in the future when interest rates may be lower. Conversion is typically effected before the cash value of the policy exceeds the amount of premiums paid (including any premiums that are to be pre-funded), which minimizes the size of the loan.

Comparing The Options

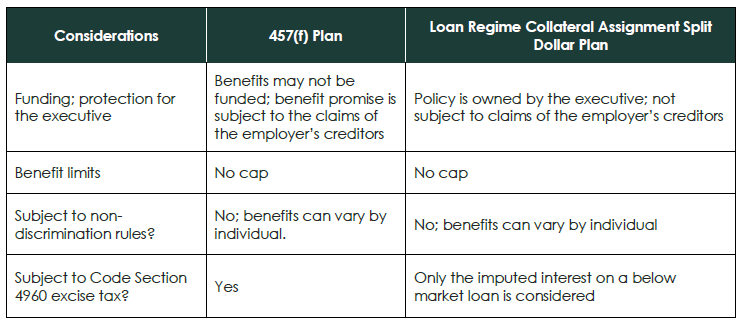

A properly designed split dollar life insurance program can be an effective retention tool and provide non-taxable benefits that may be more advantageous than a 457(f) plan. Split dollar plans are becoming much more popular in the non-profit arena. Among other considerations, a non-profit organization may wish to consider the following factors in evaluating whether to implement a 457(f) plan or a collateral assignment split dollar plan.

457(f) Overview

As discusses previously, for many years, the go-to form of supplemental retirement benefits for an executive of a non-profit organization has been a 457(f) plan. Under Section 457 of the Internal Revenue Code (the “Code”), a non-profit organization can provide supplemental retirement income to key employees through a 457(b) “eligible” deferred compensation plan or a 457(f) “ineligible” deferred compensation plan. The Code limits the annual amount that can be contributed to a 457(b) plan on behalf of an executive, so it may not be the best vehicle for providing a meaningful retirement benefit to a highly paid executive.

A 457(f) plan is not subject to an annual limit on contributions so it can be used to provide a higher level of benefits to an executive than a 457(b) plan. However, the benefits under a 457(f) plan are taxable to the executive in the first year in which the benefits are not subject to a substantial risk of forfeiture. In other words, the benefits are taxable when they first become “vested,” even if the benefits are not payable to the executive until a later date.

Example: Executive Jones becomes vested in a $1,000,000 457(f) benefit on December 31, 2022. Benefits are paid in five equal installments beginning on January 15, 2023. Executive Jones is taxed on the full $1,000,000 benefit in 2022, even though the installment payments will not begin until 2023.

For this reason, most 457(f) plans are structured as “vest and pay” arrangements, where the benefits are paid out in full within a short period after the vesting date. 457(f) plans are excellent retention vehicles because if the executive leaves before a vesting date, he/she will forfeit the entire benefit. However, a younger executive may not be willing to wait until retirement age to receive a benefit.

Benefits can alternatively be paid out before retirement as interim benefit payouts, which can be a valuable retention tool. For example, a 457(f) plan could be structured to vest and make a distribution shortly before an executive’s child starts college. The problem with early payouts, even though decreasing the risk of forfeiture, is that there may be less money available as retirement income for the executive.

Substantial Risk of Forfeiture

The key to protecting the tax deferral under a 457(f) plan is creating a substantial risk of forfeiture. A substantial risk of forfeiture means that the executive’s rights to the compensation are conditional upon the future performance of “substantial” services by the executive. Full-time work over at least a 2-year period will generally constitute a substantial risk of forfeiture.

The IRS issued proposed regulations under Code Section 457(f) in 2016. Those regulations provided some additional events that can potentially create a substantial risk of forfeiture, including a post-termination non-compete. Whether a non-compete is a substantial risk of forfeiture depends on all the relevant facts and circumstances, including the non-profit organization’s willingness to enforce the non-compete and the executive’s interest and ability to engage in the prohibited conduct.

The Code Section 457(f) proposed regulations also allowed an extension of vesting, sometimes called a rolling risk of forfeiture, if certain conditions are met, including:

- the payment is materially greater at the end of the extended vesting period;

- there is a minimum 2-year service period required; and

- the parties must agree to the extension of the risk of forfeiture at least 90 days in advance of the lapse of the original risk of forfeiture.

The rolling risk of forfeiture can be useful when an executive does not wish to retire at the originally contemplated retirement date and the non-profit organization is willing to retain the executive’s services for at least 2 additional years and provide an increased benefit. The executive will continue to be “at risk” to receive the payment until the extended vesting date.

Other 457(f) Plan Considerations

In order to protect the executive’s income tax deferral, a 457(f) plan generally cannot be funded through a trust or other funding vehicle.2 The executive has the status of a general unsecured creditor and, in the event of the employer’s bankruptcy, could lose all of his/her benefits.

A 457(f) plan is also subject to Code Section 409A, which governs most non-qualified deferred compensation plans. Most vest and pay 457(f) plans will be short-term deferrals, which keeps them outside of the strict Section 409A rules. However, if a 457(f) plan is not carefully drafted and administered, it can violate Section 409A and result in tax penalties on the executive.

Excise Tax on Excess Compensation

Perhaps even more problematic from a non-profit organization’s standpoint is the excise tax on excess compensation that was added to the Code as part of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (“TCJA”).

Under Code Section 4960, effective for taxable years beginning after December 31, 2017, a tax-exempt organization must pay an excise tax equal to the income tax rate imposed on corporations for the taxable year (21% for 2022) on:

- remuneration paid to a covered employee greater than $1 million; and

- any excess parachute payment to a covered employee (even if less than $1 million).

Covered employees who are considered for purposes of the excise tax are:

- the 5 highest-compensated executives of the tax-exempt organization for the taxable year (who are also highly compensated as defined in Code Section 414(q)); 3 and

- any employee who was a covered employee for any preceding taxable year beginning after December 31, 2016.

Remuneration for this purpose means:

- wages (excluding designated Roth contributions); and

- amounts included in income under Code Section 457(f) that are no longer subject to a substantial risk of forfeiture.

For example, if a covered employee receives wages of $1,000,000 and vests in a deferred compensation plan with a present value of $3,000,000, the covered employee has excess remuneration of $3,000,000 ($4,000,000 total remuneration less $1,000,000) and the tax-exempt organization would need to pay an excise tax of $630,000 on that excess remuneration.

Excess Parachute Payments

The excise tax on an excess parachute payment is somewhat analogous to the tax that applies to parachute payment made by a corporation that are contingent on a change in control under Code Section 280G. Unlike Section 280G parachute payments, the Code Section 4960 excise tax applies to payment of compensation to a covered employee that are contingent on a separation from service. Regulations issued by the IRS in January 2021 have interpreted the excise tax as applying only in the event of an involuntary separation from service (which can include a resignation for good reason).

The determination of whether there is an excess parachute payment is similar to the calculation under Code Section 280G. An excess parachute payment is greater than 3-times the covered employee’s base amount of pay. The base amount is the employee’s average compensation over the 5 taxable years preceding the year of

separation. If this calculation results in a parachute payment, then the excess parachute payment is the amount of the payment that exceeds 1-times the base amount (not 3-times the base amount.)

Example: CEO Smith is a covered employee (one of the top 5 highest paid employees and is a highly compensated employee). She has a 457(f) plan with a present value of $900,000 payable if she works until age 65. The benefit is payable before age 65 if Smith terminates due to death, disability or involuntary termination not for cause. On July 1, 2022, CEO Smith is involuntarily terminated and becomes 100% vested in the $900,000 benefit. CEO Smith’s base amount is $275,000 (average annual compensation in 2017-2021) and 3-times the base amount is $825,000 ($275,000 x 3). The payment of compensation that is contingent on the involuntary separation from service of $900,000 is greater than the base amount of $825,000. Therefore, the payment is a parachute payment. The excess parachute payment is $625,000 ($900,000 – $275,000) and the tax-exempt organization owes an excise tax of $131,250 (21% x 625,000).

The Code Section 4960 excise tax does not provide for any grandfathering of benefits under agreements that were in effect before January 1, 2018. For example, a tax-exempt organization will have to pay an excise tax on benefits greater than $1 million paid to a covered employee under a 457(f) plan that vests after December 31, 2017, even if that plan was in effect before January 1, 2018.

The bottom line is that the Code Section 4960 excise tax materially increases the cost to any tax-exempt organization with a 457(f) plan that is expected to provide a benefit over $1 million or that could result in an excess parachute payment.

Due to the limitations of a 457(f) plan, coupled with the extra cost potentially imposed by the Code Section 4960 excise tax, many non-profit organizations are considering split dollar life insurance arrangements as a vehicle to provide supplemental retirement benefits to executives.

Split Dollar Life Insurance

A split dollar life insurance arrangement in the employer/employee context is an arrangement where the benefits and obligations with respect to a life insurance policy are split between the employer and the employee.

The IRS issued final regulations on split dollar plans in 2003, so the rules are relatively settled. A split dollar arrangement is an arrangement between the owner and the non-owner of a policy where:

- the employer pays all or part of the premium on a policy;

- the employer is entitled to recover its premium payment from the policy; and

- the arrangement is not part of the group-term life insurance plan.

Under the final regulations, a split dollar plan is taxable under either:

- the economic benefit regime, which applies when the employer owns the policy; or

- the loan regime, which applies where the executive owns the policy.

Economic Benefit Regime

Under the economic benefit regime, the employer owns the policy and typically pays the premiums for the executive’s benefit. The death benefit is split between the employer and the executive’s beneficiaries. The employer typically recovers at least its premium payments from the death benefit.

The executive is taxed on the economic benefits of the policy, which include:

- the annual cost of the death benefit;

- the value of any policy cash values to which the executive has current access; and

- the value of any other economic benefit provided to the executive under the policy.

An arrangement utilizing the economic benefit regime is relatively straightforward to implement. A non-profit organization should be aware of the following considerations:

- as the executive gets older, the cost of the death benefit increases, which increases the amount of income the executive must recognize;

- the executive will also be taxed each year on the equity build-up in the policy if he/she has access to the policy cash value;

- the amounts taxable to the executive count as remuneration for purposes of the Code Section 4960 excise tax; and

- Code Section 457(f) does not apply as there is no deferred compensation.

A non-profit organization could agree to pay a bonus to the executive to make the executive whole for the taxes owed on the benefit; care should be taken in this event to comply with the Code Section 457(f) and 409A rules.

Loan Regime

Under the loan regime, sometimes called a collateral assignment split dollar plan, the employer makes a loan to an executive that allows the executive to purchase a life insurance policy. The loan may bear interest which accrues and compounds as provided in the loan documentation. The executive owns the policy and collaterally assigns it to the employer as security for the repayment of the loan. The loan to the executive is typically repaid to the employer from the cash surrender value or death proceeds of the policy.

The executive may be allowed to take loans from the policy, typically at retirement age, in amounts that do not impair the employer’s right to be repaid. Loans from the policy are non-taxable to the executive.

A loan to an executive under a collateral assignment split dollar agreement is similar to a mortgage loan, where the employer is the lender and the executive is the borrower.

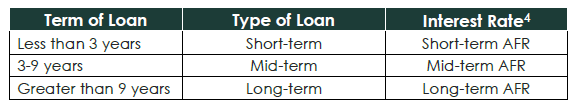

The potential tax impact to the executive depends on the term of the loan and the interest rate on the loan. If the loan does not bear interest at or above the appropriate Applicable Federal Rate (“AFR”), the loan is a below market loan under Code Section 7872 and the executive will recognize imputed income each year equal to the foregone interest on the loan.

The test for whether the loan bears sufficient interest depends on whether the loan is a demand loan or a term loan.

A demand loan is due “on demand” of the employer-lender. If the demand loan has an interest rate at least equal to the short-term AFR, the executive will not recognize any income on the loan. If the interest rate is less than the short-term AFR, or if the loan is non-interest bearing, the executive must recognize income each year equal to the short-term AFR, less any stated interest on the loan. The amount of imputed interest is determined on the last day of the calendar year. For convenience, if the loan is in effect for the entire calendar year, the employer may use the blended annual rate to calculate the imputed income for that year, which is announced by the IRS each July.

A term loan has a stated maturity date. For example, if the loan is due on the death of the executive, the interest rate will be based on the life expectancy of the executive and will typically be at the long-term AFR.

A term loan is tested for sufficient interest on the month and year in which the loan is made. In general, any imputed income on a term loan that does not bear sufficient interest is equal to the amount of the loan minus the present value of all future payments required to be made under the terms of the loan. If a new loan is made for each annual premium payment, the interest rate on each annual loan will adjust each year, which could require some complex calculations. Alternatively, when interest rates are low, the employer may decide to loan all the premiums to the executive at the time the policy is purchased to lock in the low interest rate. The premiums that are prepaid can be held in a deposit account by a financial institution or insurer, or can be used to purchase a single premium immediate annuity that will pay the subsequent premiums on the policy.

Split dollar term loans that are due at the death of the employee are generally treated for income tax purposes as hybrid demand/term loans. Under the hybrid loan rules, the loan is tested for sufficient interest on the date the loan is made, as any other term loan. However, if the loan is below market, the executive is taxed as if the loan were a demand loan. In other words, if the interest rate on a hybrid loan is less than the appropriate AFR, the executive recognizes income each year equal to the AFR (less any stated interest) multiplied by the loan balance.

Recourse v. Non-Recourse Loans

A loan is generally recourse if the employer-lender can recover the outstanding loan balance from the executive’s personal assets. A limited recourse loan is one in which the employer can pursue the executive for repayment only if the policy is insufficient to repay the loan. A non-recourse loan is one in which the employer’s right of recovery is limited to the policy cash value or death benefit and the employer agrees not to pursue the executive for any shortfall.

A non-recourse loan is treated as a contingent loan, which requires some complex calculations and results in an unfavorable interest rate on the loan, potentially increasing the amount of imputed interest on the loan. To avoid contingent payment treatment, the employer and executive must attach a written representation to their respective income tax returns for the year that the loan is made stating that a reasonable person would expect the loan to be repaid in full.

Non-Equity Arrangements

A special rule applies to a non-equity arrangement where the executive owns the policy but only has the right to death benefits under the policy (i.e., the executive has no rights to the cash value of the policy.). Under the special rule, the employer is treated as the owner of the policy (regardless of who actually owns the policy) and the executive is taxed under the economic benefit regime.

Switch Dollar Arrangements

A switch dollar arrangement begins as a “non-equity” arrangement, in which the executive owns the policy and has the right to a specified amount of death benefit. The employer pays the premiums each year and has the right to the death benefit in excess of the executive’s designated amount and all the cash value of the policy. The policy is collaterally assigned to the employer to secure the employer’s right to receive its share of the death benefits and to restrict the executive’s access to the cash value of the policy. The executive is taxed each year on the value of the death benefit.

The agreement will specify when the executive has the right to convert or “switch” the arrangement to a loan regime collateral assignment split dollar arrangement. Typically this will be prior to the projected “crossover” point (which occurs when the policy cash value exceeds the amount of premiums paid by the employer, including any premiums required to be pre-funded) or upon the executive’s earlier termination of employment or retirement.

When the executive exercises his/her conversion right, the parties enter into an amended arrangement that complies with the loan regime rules, and update the collateral assignment to reflect the terms of the amended arrangement. The executive signs a promissory note agreeing to repay the employer for the greater of the cash value of the policy or the premiums paid (including any premiums that are pre-funded,), which amount bears interest from that point. The amount of the loan should be equal to the greater of (a) the premiums paid to date (plus any additional premiums pre-funded on the date of conversion) or (b) the cash value of the policy at the date of conversion so that the executive is not taxed on the cash value of the policy at the time of conversion.

Code Section 409A Considerations

The IRS has ruled that a split dollar loan is not generally treated as deferred compensation under Code Section 409A. However, a split dollar arrangement taxable under the loan regime can result in deferred compensation for purposes of Section 409A in certain situations, for example, if interest or other amounts on a split dollar loan are waived, cancelled, or forgiven.

A split dollar arrangement that provides only a death benefit to the executive (a non-equity arrangement) is exempt from Code Section 409A as a death benefit plan. For this purpose, the imputed income on the cost of current life insurance protection is treated as provided under a death benefit plan and is exempt from Code Section 409A.

If the employer owns the policy and the arrangement is taxable under the economic benefit regime, the arrangement could provide deferred compensation if the executive has a legally binding right to economic benefits other than the death benefit (an equity arrangement) under the policy that are payable in a future taxable year and do not qualify as short-term deferrals. For these reasons, if an executive has the right to policy cash values in an economic benefit regime arrangement, the parties should carefully consider how and when the policy cash values will be made available to the executive.

Code Section 4960 Excise Tax

Only any imputed income on a below-market loan is considered for purposes of the Code Section 4960 excise tax.

Final Thoughts

A properly designed split dollar life insurance program can be an effective retention tool and provide non-taxable benefits that may be more advantageous than a 457(f) plan. Although both types of split dollar plans have advantages, in the current environment, we are seeing most plans structured either under the loan regime rules with a “below-market” loan or as a switch dollar arrangement. Among other considerations, a non-profit organization may wish to consider the following factors in evaluating whether to implement a 457(f) plan or a collateral assignment split dollar plan:

References

- The term “non-profit organization” as used in this memorandum means a tax-exempt

organization. - A 457(f) plan may be funded through a “rabbi” trust. Although it provides some protection for

executives, assets in a rabbi trust are considered to be the employer’s assets and are subject to

claims of the employer’s creditors in the event the employer becomes insolvent. - A highly compensated employee is defined by reference to Code Section 414(q), and for

2024 includes an employee who has compensation greater than $150,000 in 2023 and, if elected

by the employer, was in the top 20% of the employees when ranked by compensation. - The IRS publishes the AFRs on a monthly basis.

Co-Authored by Cynthia A. Moore, Member at Dickinson Wright PLLC

CRN202704-6293162

About the Author

Chris J. Jones, CLU®, ChFC®

Partner & Senior Benefits Consultant

Known for his analytical mindset and mathematical precision, Chris works closely with credit unions to design Supplemental Executive Retirement Plans (SERPs) that are not only durable and compliant but also grounded in data that supports long-term performance. With more than three decades in financial services, he has built a reputation for ensuring that every plan rests on solid numbers and delivers on its promise to executives and boards.

Since 2014, Chris and his team have implemented more than 200 split-dollar SERPs for credit unions and nonprofits, each one on track or exceeding its original performance projections.